I encountered two extremely different perspectives on being a caregiver in the last few days.

I encountered two extremely different perspectives on being a caregiver in the last few days.

The first was in our local Herald Tribune. Columnist Carrie Seidman wrote an article about Bob Dein, who cared for his wife after her diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. The tragedy of his experience evolved from a combination of his wife’s desire to keep it a secret and her increasing cognitive impairment.

Many people associate Parkinson’s Disease only with the tremor, or bigger movements that they see from Michael J. Fox. There are many other far more troublesome symptoms. For some, like Bob’s wife, there are delusions and psychotic behaviors, and dementia.

The article went on to describe the enormous weight Bob carried in secret and how it wore him down to the point of planning suicide. He wanted a way out and he couldn’t see any other way. Luckily, with grace, he brought his wife to the hospital and got help. Unfortunately, it appeared from the article that he still felt some guilt. “I always felt that she died thinking I didn’t do what I was supposed to do.”

and how it wore him down to the point of planning suicide. He wanted a way out and he couldn’t see any other way. Luckily, with grace, he brought his wife to the hospital and got help. Unfortunately, it appeared from the article that he still felt some guilt. “I always felt that she died thinking I didn’t do what I was supposed to do.”

While my situation is no where near as grim there have been times where the thought of suicide fleetingly appeared, along with running away to a foreign country. I never planned it, I never actively considered it. But it came along with the moments I thought “I can’t do this anymore, I just can’t.”

Thankfully, it helps that we have at times taken advantage of support groups, some run by the Neuro Challenge Foundation where Bob Dein is now putting his experience to good use as a board member. We, unlike Bob, are not isolated.

I feel lucky compared to Bob in our situation of caregiving. From day one Larry has been open about his disease. He said he wanted to tell, because if it had been the other way around he’d want to know. We talk about it early and often, to family, friends, sometimes even strangers if there’s a reason to explain why he looks or behaves differently. Sharing prevents isolation, and helps others understand.

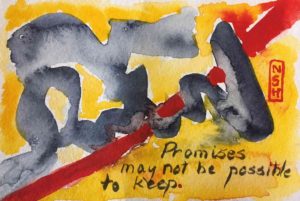

I read on some of the online discussion groups that there are many people who don’t want anyone to know. Of course, that is ludicrous. The outward signs of neurological diseases make others wonder about you when you walk differently, talk differently, or your facial expressions change. Absent knowing, they make up a story – maybe he’s an alcoholic, or on drugs, or mentally ill, etc. I also read about others who promise they will never put their loved one in a nursing home.

I’m lucky in that he’s still Larry. His personality hasn’t changed. He has no psychosis, no dementia. He only had hallucinations for three days as a result of a medication that we immediately stopped. He still has a sense of humor. Caring for your loved one who isn’t really the same person you loved must be brutally hard.

On the other end of the caregiving spectrum is someone who was visiting with us. For three months, he gave full time care at home to his first wife who had cancer and was paralyzed by it. He described it as his finest hour. He is a very spiritual man and felt that the worse his wife became the more spirituality was required of him. I guess I think of it as grace. Even he and his wife, at some point, realized he could no longer do it alone as her condition progressed. And three months is different than many years.

There is no glory or grace in being a caregiver for me. If we had all the money in the world, I’d hire someone wonderful to do the caregiving so I could just be the wife. But we don’t, so I’m the caregiver. A sometimes begrudging caregiver, mostly loving caregiver, but a reluctant caregiver nonetheless. I’m just not much of a nurturer, and I’m certainly no martyr.

Someone said to Larry in my presence, “you know you’re not a burden to her.” I disagreed.

“Of course he’s a burden, or at least his disease is a burden,” I said. “Let’s not sugar coat this.” The person looked dismayed. “It’s a burden I am choosing, now, because I love him,” I went on to say. “I know he would do it for me in a heartbeat.”

There may come a day, however, when the burden will be too much, that we will have to consider other options, including a nursing home, as hard as that decision might be. I can’t promise it will never happen. I only hope that if I can’t see the time has come that someone else will help us see it.